Eating the banks' lunch: Why alternative debt is no longer so alternative for lower mid-market private equity

“Alternative lending isn’t looking so alternative anymore,” reckons law firm Vinson & Elkins, which services the private equity sector.[1]

This is particularly true when it comes to private equity firms raising debt capital. Alternative – also known as direct – lending is the fastest growing asset class in this space, according to research from Deloitte, with such lenders raising consistently larger funds: “With more capital to deploy, direct lenders are now writing larger tickets and expanding into areas previously dominated by the banks.”[2]

In Europe, the amount of private debt financing provided by banks has fallen from about 80% around the time of the financial crisis to 25% today. “Banks face more competition in the debt markets than ever,” according to Investment Pensions Europe magazine back in 2014.[3] The intervening years have only seen that competition strengthen.

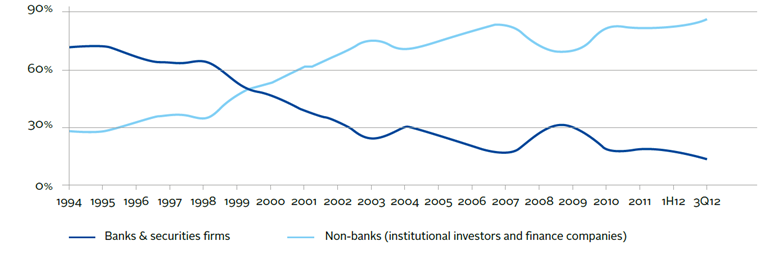

This is far from being a novelty, as the US has long had a strong alternative finance sector and, while it’s grown over the past decade, it was thriving well before that. That this is a trend which began before the crisis is indicated by the related debt market of leveraged loans, where global non-bank provision overtook that of banks at the end of the last century (see chart below).

Bank and non-bank lending for leveraged loans from 1994 to 2012

Source: S&P Capital IQ LCD

Source: S&P Capital IQ LCD

Private equity has seized on this burgeoning source of finance. Some 47% of private equity funds launched since 2010 have taken up subscription credit facilities offered by alternative finance, according to Preqin, compared to just 13% of funds launched before that date.[4]

What’s driving it?

One important factor in this trend has been that banks are lending less. Firms’ requirement for loan capital hasn’t diminished – banks’ readiness to lend has. They have reduced lending in order to meet the EU’s regulatory capital requirements – encapsulated in Basel II and III regulations – by deleveraging, particularly to client sections that are seen as riskier. Lower mid-market PE firms seeking debt finance fall within this definition.

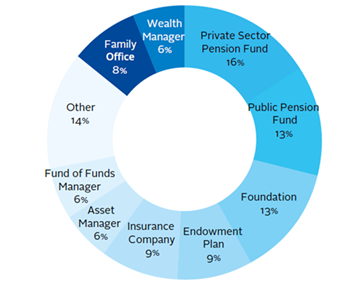

As a result of this unfulfilled demand, alternative lenders have stepped in. They are often backed by quality institutional investors seeking to increase yield in an ultra-low interest rate world, alongside diversification away from more traditional fixed income asset classes. Pension funds, insurance companies and family offices are some of the biggest investors in this space.

For example, ThinCats has ongoing capital commitments from BAE Systems Pension Scheme, Insight Investment, Waterfall Investment Management, ESO Capital, and British Business Investments, the commercial subsidiary of the British Business Bank. ThinCats’ panel of institutional funders have provided up to £700m. Alternative debt providers are seeing an increasingly diversified lender base, providing patient capital to corporate borrowers (see chart below).

Private debt market, by investor category

Source: Preqin Private Debt Spotlight, March 2018

Source: Preqin Private Debt Spotlight, March 2018

Increasingly dominant in PE

Alternative lenders are taking an ever-increasing share of this market in Europe. “This in itself is not new,” notes Deloitte, “but what is interesting is that they are beginning to seriously penetrate markets that are dominated by traditional bank lenders”. For example, alternative finance deployment in this space was steady, year-on-year, at c€22.6bn in H1 2019. However, this followed an exponential increase in alternative lending of €16.7bn, €26.8bn and €38.1bn in 2016, 2017 and 2018 respectively, according to the consultancy.[5]

According to lawyers Vinson & Elkins, the US mid-market PE direct lending market has ballooned to $910bn, in what was previously considered a “backwater”. Again, this is a global phenomenon, not a peculiarity of the US.

Direct lending via the medium of funds has, of course, been around for some time. However, it has historically been focused on the mid-market upwards. Direct lending funds, and the institutional capital lent through them, has not ventured down the cap scale. The reason for this is that, previously, the level of expertise and analysis to do this has made it uneconomical for alternative lenders, given the level of due diligence for a lower mid-market loan is pretty much the same as for a significantly larger deal.

This is changing. Institutional-quality loan capital is increasingly being made available to the lower-mid market. This is a function of both the maturity of alternative lending as an asset class – which naturally focused on the larger deals early on – and the increasing capability of technology, in the form of big data, machine learning and the like, to provide robust analysis of the market.

For example, ThinCats, supported by its proprietary credit model and experienced origination and underwriting teams, is able to provide the benefits of direct lending capital to areas of the market that were previously wholly reliant on the banks.

[1] https://plus.velaw.com/2019/02/15/as-alternative-lending-goes-mainstream-3-things-you-need-to-know/

[2]/[4] Deloitte Alternative Lender Tracker, Autumn 2019, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/corporate-finance/deloitte-uk-aldt-autumn-2019d.pdf?nc=1

[3] https://www.ipe.com/credit-debt-markets-and-private-equity/10007791.article

[5] Private Equity Managers Are Increasingly Turning to Loans Instead of Investors, https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b1ft12gp9lsv00/Private-Equity-Managers-Are-Increasingly-Turning-to-Loans-Instead-of-Investors