The challenge for the 'challengers'

It’s no secret that the reputation of the main high street banks has been eroded over the past few years, not least in the eyes of those running small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). And, while the new wave of challenger banks have been heralded as saviours, they are beset by many of the same underlying problems as their older, larger siblings.

But even new challenger banks may not be the best solution for SMEs’ lending needs because … well, because they’re banks.

Big banks

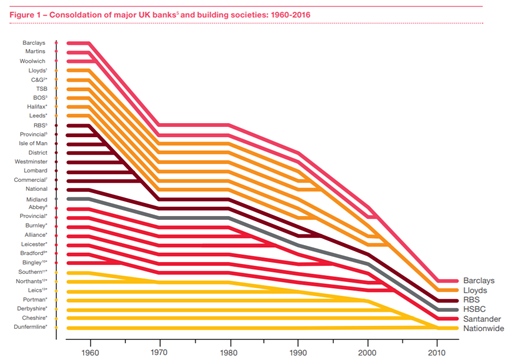

Some of the problems that SMEs face in accessing capital date back decades. Basically, lenders got too big. Like anything that has a market power, they used it: “By 2010, the market concentration reached new heights across retail banking products. The six large banking groups held an 89% market share of the current account market…[1] In parallel with increased concentration, the banking market experienced relatively low customer satisfaction, as highlighted in a 2013 survey in which retail banking customers rated the main high street banks negatively for satisfaction.”

Since the crisis, low rates have squeezed banks’ margins, while “stringent regulatory capital requirements, high remediation provisions and increased ongoing compliance costs contributed to a tough backdrop that has caused European banks to earn returns below their cost of equity since 2008.”, according to Deloitte. Overall, this has caused banks to pull in their horns. While they still command the biggest market share, they’re not dominant everywhere like they used to be: they can’t afford to be.

A solution is badly needed. By the end of 2018, there were 5.7m UK SMEs: up 1.4m on the previous decade. That’s a lot of businesses that will, at one time or another, need capital. If they don’t get it when needed, the implications for them and the wider economy are considerable.

A recent roundtable by the Financial Stability Board expressed “concern that banks may have increased the pricing and the proportion of secured SME lending – as well as reduced credit to riskier firms – as a result of the reduced eligibility of collateral for regulatory capital purposes.” Other concerns “included accounting rules (IFRS 9), which may incentivise banks to reduce the maturity of SME loans, to request higher collateralisation, and to reduce credit availability in a downturn”. This means that “large banks may be incentivised to focus on bigger loans … making it harder for smaller SMEs to obtain financing overall”.

Vive la revolution

In order to address this, UK and European regulators have unleashed a raft of reforms to open up the market, particularly the advent of Open Banking in early 2018. This standardised the online applications and procedures that banks use to make payments and access information. All company apps and websites can now ‘talk’ to banks using the same language. Not only are they able to, but they are required to – opening up the playing field to newcomers able to access information that was previously the property of a handful of banking behemoths.

This ability to analyse rich data used for pricing specialised risks “could transform the way specialised lenders operate.”[2] Business and consumer lending – which was before the start of last year pretty much a closed shop – has been blown wide open. Enter the competition.

Little banks

According to analysts, a major advantage for borrowers is that new specialist banks are now “able to price risk on an individual basis in a way that is more difficult for larger, more automated providers. Many have experienced management teams, who have operated across the full spectrum of UK banking. Their relatively small size also means they are better able to manage certain types of risk. These factors mean they are able to provide differentiated services and competitive offers to their customers.”[3] Examples include the new range of digital-only banks that are “typically built in a modular way, positioning the banks to take advantage of the Open Banking trend by readily integrating functionality and data from other sources”.

More competition on the supply side means a better deal for those on the demand side. However, there are limits to which a bank can go.

The recent and high-profile misfortunes of the largest challenger – Metro Bank – encapsulate the difficulties that any bank faces, however new and shiny. Earlier this year, Metro announced £350m capital raising, because of “an accounting scandal that revealed up to £1.7bn of its loans are far riskier than it had claimed. That left it needing extra capital to hold against the loans.”

The reason it’s had to do this takes us back to the earlier, and fundamental, issue of “stringent regulatory capital requirements”.

Basel

After the global financial crisis regulators recognised that banks posed systemic risk to the financial system, and to the wider economy, if they take on too much risk.

In simple terms, if banks make bad loans, this threatens the assets of their depositors. If you run a bank, you are covered by these regulations: whether high street, or digital-online-only – it doesn’t matter: rules are rules. Hence the bind that Metro found itself in. All banks face restrictions on the risk capital they can have on their books, and SME lending is right up there in the category of ‘risk capital’, whether you like it or not. A challenger bank may have better processes, but the same regulations means it faces harder lending constraints of SMEs as, say, RBS.

The real revolutionaries

There are, however, alternatives – one does not have to have a banking licence in order to be a lender. If you don’t have deposit accounts, you are not a bank. And this is one area that the revolution in regulation has really opened up the field. Alternative finance firms that do not have depositors to protect – for instance, those who provide capital from institutional and retail investors – are not bound by such regulations.

While some of those companies may seem to simply rely on clever software and algorithms, others also have a wealth of experience to draw on: many who have come from the banking world, where they find their skills can no longer be fully employed. The potential big win for SMEs looking for capital from all this is that they have the ability to work with people who understand their business needs and are able to make lending decisions based on the quality of their business case, not the requirement to protect depositors.

The challenger banks cannot escape the challenges of the big banks. The real challengers are the specialist SME altfin lenders.

[1] Who are you calling a ‘challenger’? How competition is improving customer choice and driving innovation in the UK banking market, PwC, 2017

[2] The future of banking is open How to seize the Open Banking opportunity, PwC, 2018

[3] Who are you calling a ‘challenger’? How competition is improving customer choice and driving innovation in the UK banking market, PwC, 2017